Understanding APIs and REST API

API (Application Programming Interface)

- A software intermediary that allows two applications to talk to each other.

- Each time we use an app like Facebook, send an instant message, or check the weather on our phone, we are using an API.

Example:

- When we use an application on our mobile phone, the application connects to the Internet and sends data to a server.

- The server then retrieves that data, interprets it, performs the necessary actions and sends it back to our phone.

- The application then interprets that data and presents us with the information we wanted in a readable way.

- This is what an API is - all of this happens via API.

Restaurant Analogy:

- Imagine we are sitting at a table in a restaurant with a menu of choices to order from.

- The kitchen is the part of the “system” that will prepare our order.

- What is missing is the critical link to communicate our order to the kitchen and deliver our food back to our table.

- That’s where the waiter or API comes in.

- The waiter is the messenger – or API – that takes our request or order and tells the kitchen – the system – what to do.

- Then the waiter delivers the response back to us; in this case, it is the food.

Provides Layer of Security

- Our phone’s data is never fully exposed to the server, and likewise the server is never fully exposed to our phone.

- Instead, each communicates with small packets of data, sharing only that which is necessary—like ordering takeout.

- We tell the restaurant what we would like to eat, they tell us what they need in return and then, in the end, we get our meal.

- APIs have become so valuable that they comprise a large part of many business’ revenue.

- Major companies like Google, eBay, Salesforce, Amazon, and Expedia are just a few of the companies that make money from their APIs.

The Modern APIs

Over the years, what an API is has often described any sort of generic connectivity interface to an application. More recently, however, the modern API has taken on some characteristics that make them extraordinarily valuable and useful:

- Modern APIs adhere to standards (typically HTTP and REST), that are developer-friendly, easily accessible and understood broadly.

- They are treated more like products than code. They are designed for consumption for specific audiences (e.g., mobile developers), they are documented, and they are versioned in a way that users can have certain expectations of its maintenance and lifecycle.

- Because they are much more standardized, they have a much stronger discipline for security and governance, as well as monitored and managed for performance and scale

- As any other piece of productized software, the modern API has its own software development lifecycle (SDLC) of designing, testing, building, managing, and versioning. Also, modern APIs are well documented for consumption and versioning.

REST ( REpresentational State Transfer)

- There is a transfer of representation of resources.

- When a client request for a resource from the server, the server doesn’t actually deliver the resources, it doesn’t actually send the database that it has but rather a representation of that resource in a format that is readable HTML or image.

- So think of actual resources, physical things located on a web server database or web server hard drive and representations of those resources as copies in either readable format for human being like HTML or image or easy to work with formats for programmers like JSON, XML and others.

Resources:

- It can be pretty much anything on the internet. Examples: user, list of users, photo, list of photos, comments, posts, articles, pages, videos, books, profile etc.

Uniform Resource Identifier (URI):

- Anything or everything present on the web can be considered as resources which is identified by

URI. - It is a string of characters designed for unambiguous identification of resources and extensibility via the URI scheme.

- Such identification enables interaction with representations of the resource over a network, typically the World Wide Web, using specific protocols.

- Schemes specifying a concrete syntax and associated protocols define each URI.

- The most common form of URI is the Uniform Resource Locator (URL), frequently referred to informally as a web address.

REPRESENTATIONAL STATE TRANSFER

- REST, or REpresentational State Transfer, is an architectural style for providing standards between computer systems on the web, making it easier for systems to communicate with each other.

- REST-compliant systems, often called RESTful systems, are characterized by how they are

statelessandseparate the concerns of client and server.

SEPARATION OF CLIENT AND SERVER

-

Implementation of client and server can be done independently without each knowing about the other. This means that the code on the client side can be changed at any time without affecting the operation of the server, and the code on the server side can be changed without affecting the operation of the client.

-

As long as each side knows what format of messages to send to the other, they can be kept modular and separate. Separating the user interface concerns from the data storage concerns, we improve the flexibility of the interface across platforms and improve scalability by simplifying the server components. Additionally, the separation allows each component the ability to evolve independently.

-

By using a REST interface, different clients hit the same REST endpoints, perform the same actions, and receive the same responses.

STATELESSNESS

-

The server does not need to know anything about what state the client is in and vice versa. In this way, both the server and the client can understand any message received, even without seeing previous messages. This constraint of statelessness is enforced through the use of resources, rather than commands.

-

Because REST systems interact through standard operations on resources, they do not rely on the implementation of interfaces.

-

These constraints help RESTful applications achieve reliability, quick performance, and scalability, as components that can be managed, updated, and reused without affecting the system as a whole, even during operation of the system.

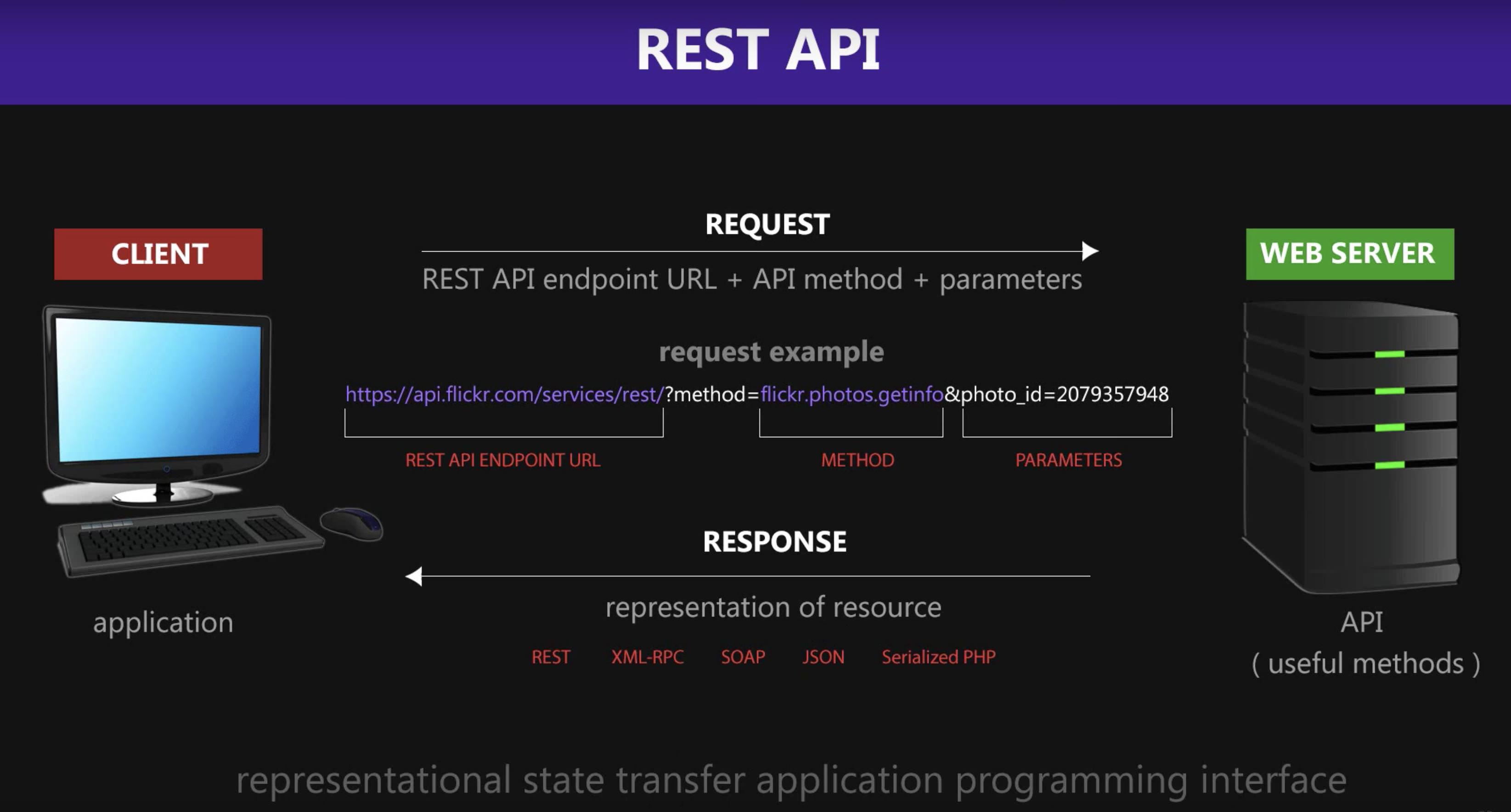

COMMUNICATION BETWEEN CLIENT AND SERVER

In the REST architecture, clients send requests to retrieve or modify resources, and servers send responses to these requests.

MAKING REQUESTS

REST requires that a client make a request to the server in order to retrieve or modify data on the server. A request generally consists of:

- an HTTP verb: which defines what kind of operation to perform

- a header: which allows the client to pass along information about the request

- a path to a resource

- an optional message body containing data

HTTP VERBS

There are 4 basic HTTP verbs we use in requests to interact with resources in a REST system:

- GET — retrieve a specific resource (by id) or a collection of resources

- POST — create a new resource

- PUT — update a specific resource (by id)

- DELETE — remove a specific resource by id

HEADERS AND ACCEPT PARAMETERS

- In the header of the request, the client sends the type of content that it is able to receive from the server.

- This is called the

Accept field, and it ensures that the server does not send data that cannot be understood or processed by the client. - The options for types of content are

MIME Types(or Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions)

MIME Types are used to specify the content types in the Accept field, consist of a type and a subtype.

They are separated by a slash (/).

- text - text/html, text/css, text/plain(default)

- image — image/png, image/jpeg, image/gif

- audio — audio/wav, image/mpeg

- video — video/mp4, video/ogg

- application — application/json, application/pdf, application/xml, application/octet-stream

GET /articles/23

Accept: text/html, application/xhtml

- The Accept header field in this case is saying that the client will accept the content in text/html or application/xhtml.

PATHS

- Requests must contain a path to a resource that the operation should be performed on.

- In RESTful APIs, paths should be designed to help the client know what is going on.

- Paths should contain the information necessary to locate a resource with the degree of specificity needed.

- A path like

fashionboutique.com/customers/223/orders/12is clear in what it points to, even if we’ve never seen this specific path before, because it is hierarchical and descriptive. - We can see that we are accessing the order with

id 12for the customer withid 223.

SENDING RESPONSES

CONTENT TYPES

- In cases where the server is sending a data payload to the client, the server must include a content-type in the header of the response.

- This content-type header field alerts the client to the type of data it is sending in the response body.

- These content types are MIME Types, just as they are in the accept field of the request header.

- The content-type that the server sends back in the response should be one of the options that the client specified in the accept field of the request.

Example: when a client is accessing a resource with id 23 in an articles resource with this GET Request:

GET /articles/23 HTTP/1.1

Accept: text/html, application/xhtml

The server might send back the content with the response header:

HTTP/1.1 200 (OK)

Content-Type: text/html

This would signify that the content requested is being returning in the response body with a content-type of text/html, which the client said it would be able to accept.

RESPONSE CODES

- Responses from the server contain status codes to alert the client to information about the success of the operation.

- As a developer, we do not need to know every status code (there are many of them), but we should know the most common ones and how they are used:

Status code Meaning

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

200 (OK) Successful HTTP requests.

201 (CREATED) An HTTP request that resulted in an item being successfully created.

204 (NO CONTENT) Successful HTTP requests, where nothing is being returned in the response body.

400 (BAD REQUEST) Request can't be processed coz of bad request syntax, excessive size, or another client error.

403 (FORBIDDEN) The client does not have permission to access this resource.

404 (NOT FOUND) The resource could not be found at this time. It is possible it was deleted, or does not exist yet.

500 (INTERNAL SERVER ERROR) The generic answer for an unexpected failure if there is no more specific information available.

- For each HTTP verb, there are expected status codes a server should return upon success:

- GET — return 200 (OK)

- POST — return 201 (CREATED)

- PUT — return 200 (OK)

- DELETE — return 204 (NO CONTENT) If the operation fails, return the most specific status code possible corresponding to the problem that was encountered.